Earlier this week, the West Virginia Center on Budget and Policy examined the fiscal impact of the proposed compromise tax plan between Governor Justice and Senate leadership that will influence how the budget is finalized. It appears House leadership is saying “nope” to this plan and it is unclear how the plan would close the state’s looming budget gap of $500 million for FY 2018, since a corresponding budget plan hasn’t been put forth. As we noted in our recent report on the budget, the state budget that passed – and was later vetoed by the Governor – included about $90 million from the Rainy Day Fund and no new revenue increases, along with significant cuts to the Governor’s proposed budget, including Medicaid, higher education, and other programs.

As Phil Kabler notes in the Gazette-Mail, it is also unclear what is currently included in the so-called compromise tax plan being advanced by Governor Justice. It has been rumored the tax plan is the same as Senator Fern’s amendment to SB 484 with the exception that the plan includes the Governor’s tiered severance tax rate changes and not the ones in the Fern’s amendment that significantly reduce severance tax collections. If this is true, the revenue impact to the budget would be significantly reduced. (For more detailed account of the Ferns Amendment aka the proposed compromise tax plan, see our previous post here)

According to estimates provided by State Tax Department (via email), the proposed severance tax changes in the Fern’s Amendment would result in a loss of an estimated -$135 million in severance tax collections in FY 2018 and between -$140-$150 million thereafter. Overall, the net result of the Ferns Amendment on the General Revenue Fund, according to the State Tax Department, is an increase of +$50 million in revenues in FY 2018, and a net reduction of an estimated -$170 million in FY 2019 and FY 2020, and a reduction of -$220 million by FY 2021.

For FY 2018, this includes +$280 million in sales tax increases (7 percent rate and broader base), +$49 million in additional revenue from the new and temporary CAT or commercial activities tax (0.045 percent) and high-income tax surcharge, an increase of +$12 million from ending sales tax transfer to Road Fund from sales tax collected on highway construction, and approximately -$156 million less in personal income tax collections. (Note: The reduction in the personal income tax is -$380 million upon full impact. The income tax reductions do not begin until January 1, 2018, while the other tax changes take effect July 1, 2017 – the beginning of FY 2018 – but start June 1, 2017). It is also important to keep in mind the CAT and high-income tax surcharge expire on July 1, 2020 or the beginning of FY 2021).

If the severance tax changes in the Ferns Amendment are swapped for the Governor’s proposed severance tax rates that are estimated to be close to revenue neutral, this means that the net revenue impact on the General Revenue Fund would be an increase of +$185 million ($50m + $135m) in FY 2018, then a decrease of -$30 million in FY 2019 and FY 2020, and then a reduction of -$70 million by FY 2021 assuming there is no phase-down of income tax rates.

While incorporating the Governor’s severance tax proposals into the tax compromise plan provides a significant revenue boost during the FY 2018 budget year, the sharp reductions in the income tax when it is fully implemented leads to revenue losses beginning in FY 2019 that will grow the state’s budget deficit and lead to additional cuts to vital programs and services. These declines will grow more over time, with the phase down of the income tax and the expiration of the CAT and high-income surcharge by July 1, 2020.

When all of the tax changes are fully implemented in their first year (not including sales tax transfer from Road Fund), it adds up to $280 million in additional sales tax increases, $49 million in increased revenues from the CAT and high-income surcharge, and $380 million in cuts to the personal income tax. This means the proposed compromise tax plan is actually reducing taxes on West Virginians upon full implementation, not increasing them when it comes to the General Revenue Fund budget.

While the compromise tax plans leads to one year of positive revenue growth for the General Revenue Fund and growing deficits thereafter, the proposed revenue changes to the State Road Fund would increase revenues by about +$130 million in FY 2018 and +$138 million thereafter (if you do not include the transfer of sales tax collections from the Road Fund to the General Revenue Fund).

Altogether, the revenue changes in the proposed tax compromise plan – including General Revenue and State Road Funds – increase state revenues by approximately $315 million in FY 2018 and $108 million in FY 2019. To be clear, these estimates are subject to change at any time since there is no agreed upon tax bill or a full disclosure of what is being proposed between the Governor and legislative leadership.

The overall impact of these tax and revenue changes on households in West Virginia is the same as as has been reported in previous post, which did not include any severance tax changes because the tax is mostly exported out of the state and unable to be modeled because of difficulties obtaining proper information for the process.

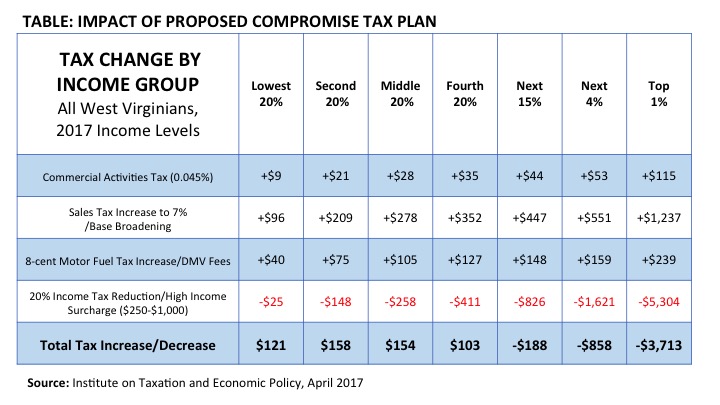

Upon full implementation – which does not include any phase down of the income tax rates or the expiration of the CAT or high-income surcharge – the proposed tax and revenue changes would, on average, increase taxes on 80 percent of West Virginia households making below $84,000 per year, while lowering them on the 20 percent of West Virginians that make more than $84,000 per year. Those making on average $11,000 per year would see their annual taxes rise by $121 or 1.1 percent of their income, while those making on average $778,000 (top 1 percent) per year would see an average tax cut of $3,713.

This means that the compromise tax plan – if this is in fact it – raises taxes on most West Virginians to help pay for tax reductions for higher-income West Virginians while leaving some revenue to spare in the first year.

The table below breaks out the tax changes for each income group in West Virginia. It includes the full-implementation of income tax reductions in 2018 and the high-income surcharge. While every income group sees an increase in their taxes from the proposed changes to the sales tax, motor fuel tax/DMV fees, and the new commercial activities tax, the large personal income tax reductions mostly goes to the top income groups. In fact, approximately 59 percent of the more than $364 million in income tax cuts go to the top 20 percent, according to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy. This is why higher income West Virginians are estimated to receive an overall reduction in taxes while low and middle-income West Virginians see an increase in taxes.

A closer look at the proposed changes to the income tax illuminate this point further. The proposed tax compromise plan condenses the state’s five income tax brackets into three brackets and reduces the rates. For example, instead of a top marginal tax rate of 6.5 percent on income over $60,000, the tax compromise proposal replaces this rate with a top rate of 5.45 percent on income over $35,000. This change will benefit those who have more income.

A closer look at the proposed changes to the income tax illuminate this point further. The proposed tax compromise plan condenses the state’s five income tax brackets into three brackets and reduces the rates. For example, instead of a top marginal tax rate of 6.5 percent on income over $60,000, the tax compromise proposal replaces this rate with a top rate of 5.45 percent on income over $35,000. This change will benefit those who have more income.

As the chart below highlights, the personal income tax in West Virginia is based on the ability to pay. This is largely because personal income tax rates increase as income increases. Sales taxes on the other hand, are regressive, taking a larger share of income from low- and middle-income West Virginians. And because those at the bottom and middle spend more of their income on necessities than the wealthy, shifting from the income tax to a greater reliance on sales taxes is a shift in “who pays” from those with more income to those with less income. Phasing out West Virginia’s income tax would also make the state’s upside down state and local tax system even more regressive over time.

As discussed in a recent report, shifting from the income tax to the sales tax is a poor strategy for economic growth. Academic research and real-world evidence from other states show that there is little evidence that such a shift will significantly boost economic growth, attract more people, or grow small businesses. However, there is compelling evidence that the income tax is a more reliable source of income than the sales tax over the long-term and that the states with more regressive tax structures increase income inequality.

As the Governor and legislature work out a compromise on the budget, including tax changes, they should keep in mind that setting West Virginia on a path of further cuts and just one year of revenue gain is not going to help build a stronger West Virginia where communities can thrive. While it is great to invest additional resources in our state’s crumbing roads and bridges, those gains could be washed away be shortchanging our state’s other needs – including our public colleges, schools, public safety, and health-care services.

Just any tax plan is not a good tax plan. It must be grounded in realistic assumptions and be sustainable over time. A sound plan cannot rely on false claims about trickle-down economic growth or a sudden surge in coal mining or natural gas extraction. It must provide a reliable source of revenue that can pay our state’s debts and sustain public investments.

As developments of the tax and budget compromise unfold, we will continue to analyze and review them as they are released to the public.