Con’t from previous post:

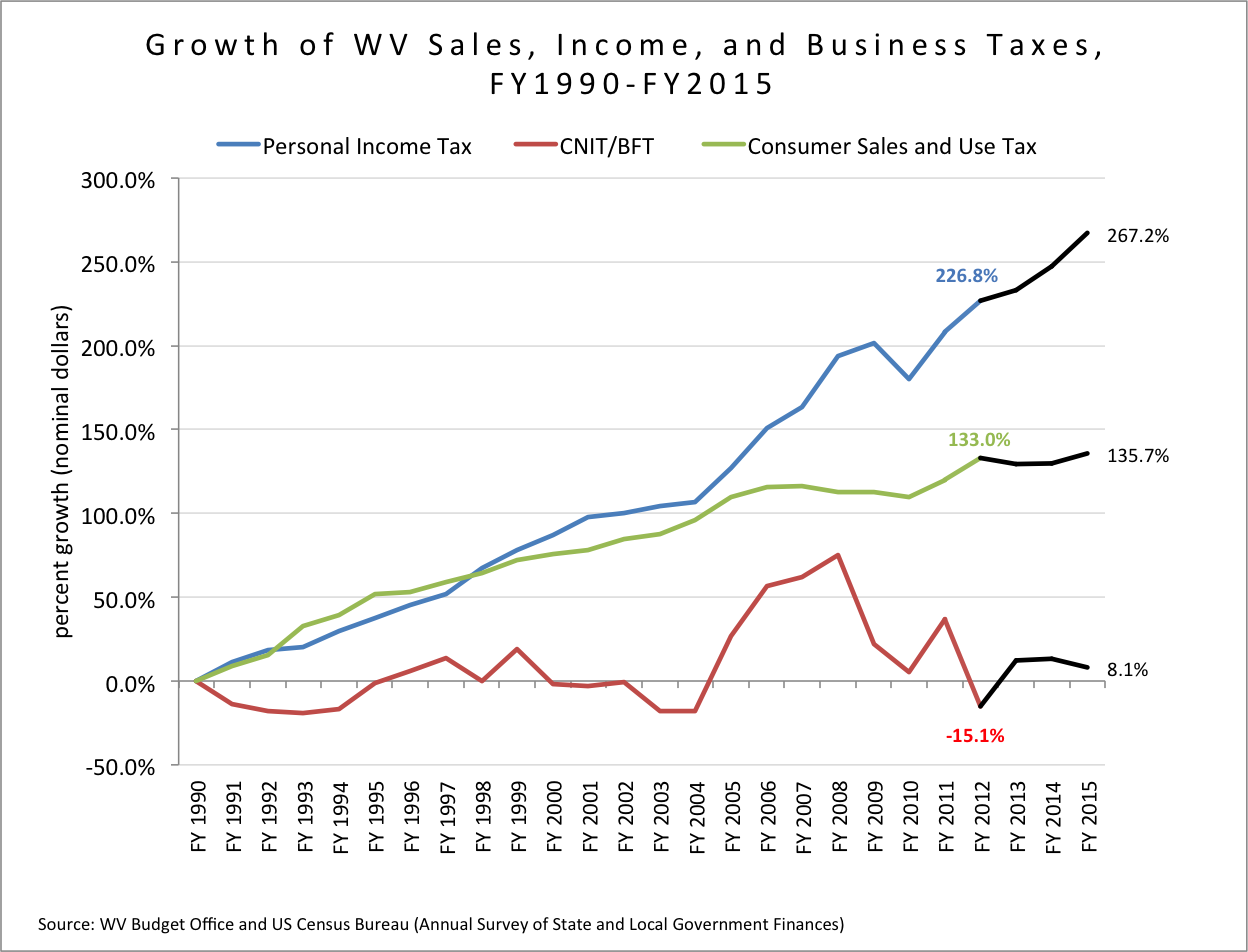

Another way to put these corporate tax cuts in perspective is by comparing the growth in corporate taxes with the growth in sales and personal income taxes over the last two decades. While personal and sales and use taxes have more than doubled from FY1990 to FY2012, the corporate net income and business franchise tax has shrunk by 15 percent. (Some of the early decline in business taxes in the early 1990s was because the state enacted “super tax credits” in the mid-1980s that depressed the growth of the tax. Many of these

credits where eventually phased out.) Notice that the recent decline in business tax growth began in FY2008, the same time as the business tax cuts were being phased in (see table above and chart below).

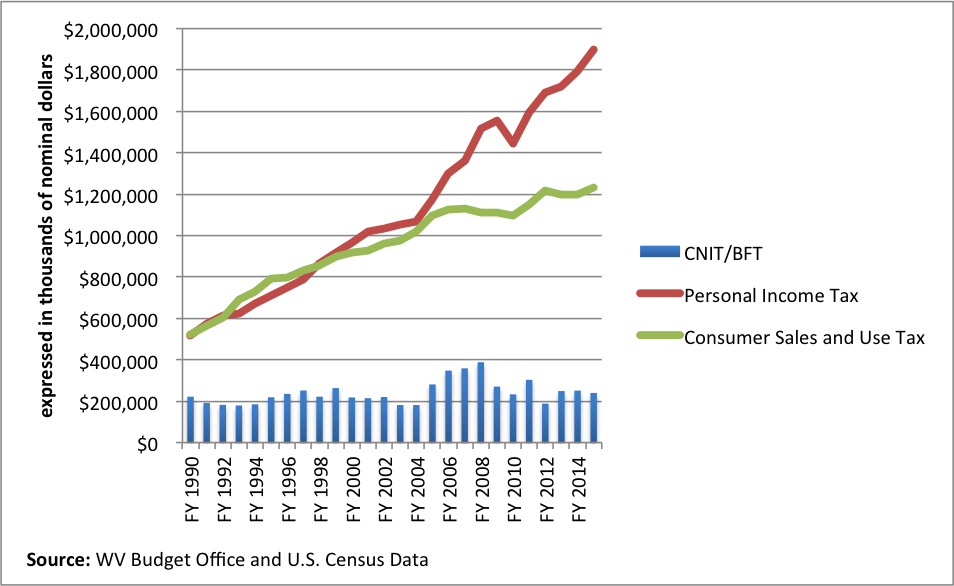

In fact, the state collected $188 million in revenue from business taxes in FY2012 compared to $222 million in FY1990, two decades ago. From 2008 to 2012, business tax collections have declined by $100 million while sales tax collections have grown by $106 million and personal income taxes by $170 million. (One reason for the slow growth of the sales tax is the reduction in the food tax, more on that below).

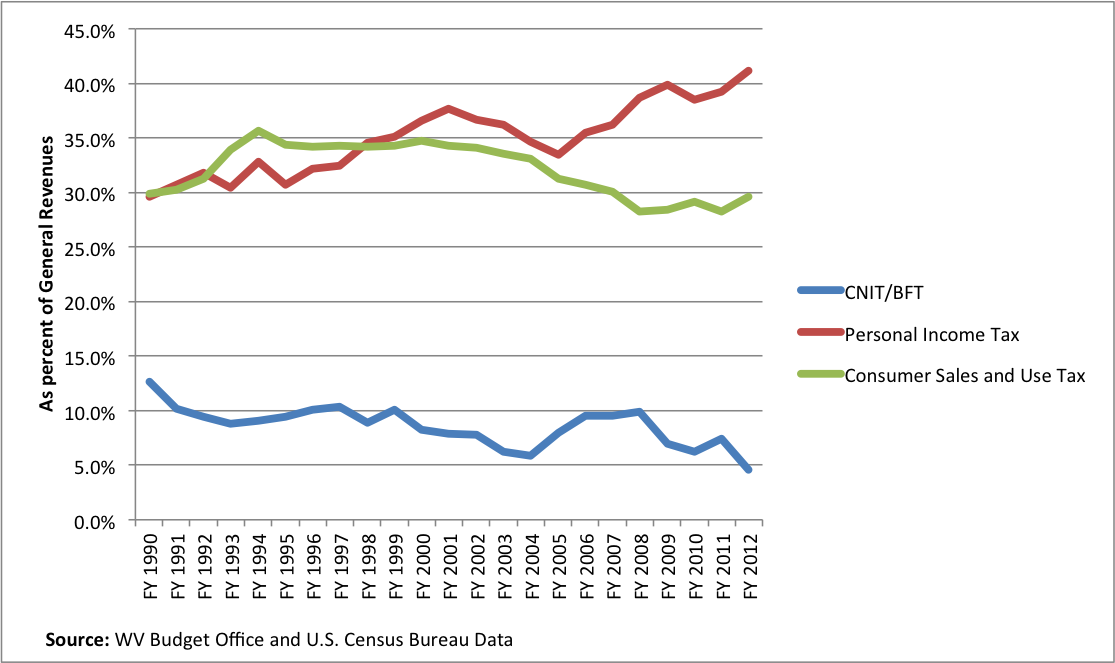

The declining business tax base can also be examined by looking at its share of general revenue collections. In FY1990 the corporate net income and business franchise tax comprised about 13 percent of general revenue tax collections compared to just under 5 percent today. In 2008, it made up just under 10 percent. Meanwhile, the sales tax has also shrunk as a share of general revenues (see chart below).

While there are many factors that have led to the decline in business taxes as a share of the budget – including recent growth in severances tax

collections – the fact remains that the business tax base has shrunk dramatically over the past few years. No matter how you slice it –

whether comparing it to the growth of other taxes, actual revenues, or as a share of the budget – business tax collections are becoming a

smaller part of the revenue our state needs to fund important programs and services.

The reduction in the sales tax on food – whether you are for or against it – has also played a role in our budget gap because the state never replaced the lost revenue. Since 2006, the state has been gradually reducing the tax from 6 percent and it is scheduled to be eliminated by July of 2013. According to WV Tax Department, every 1 percent drop in the tax rate results in $26 million in lost general revenue. This means that it will reduce our sales tax revenue by an estimated $156 million in FY2014. While taxing food is a very regressive tax on low-income families, the revenue should have been replaced if we want to balance our budget.

Over the last decade the state also lost revenue from not decoupling from federal tax changes. For example, in 2000 the state collected $21 million from the estate tax. Now the state collects zero revenue from the estate tax because it did not decouple like so many other states did ten years ago. Today, 22 states have inheritance taxes.

If you add up the cost of the corporate tax cuts ($120 million), food tax reductions ($156 million), and the estate tax ($18-21 million), you can see that close to three fourths of the FY2014 budget gap could be resolved. And this doesn’t include the dozens of bills passed over the last decades that have reduced revenue. And to be fair, it doesn’t include other legislation that has created new programs or services without dedicated revenue.

As Paul Krugman often quips, we are beginning to become the Cassandra of WVa budget issues. Over the past couple of years, we have warned

policymakers and others about the ramifications of cutting taxes without replacing the revenue. (see here, here, here, here, here, here, here, and here). In fact, in one of our very first reports in 2008 on the cuts to business taxes we concluded:

Last year, significant reductions were made to the business franchise tax without replacing the revenue lost to the General Revenue Fund, and the same course of action is being pursued today. The additional cuts in business taxes embodied in SB 465 and SB 680 threaten to significantly undermine the ability of the state to provide quality public services. Some combination of a sharp drawing-down of the states reserves, reductions in state services, and increases in other taxes seems almost inevitable during the next decade.

In acting upon SB 465 and SB 680, it is important for policy makers to consider the fiscal implications not just on a short-term basis but also for the long term. It is in the “out” years that state policymakers will have to make some difficult choices concerning whether to raise taxes or cut government services. In the end, policymakers should balance the short-term marginal effects of cutting taxes for businesses against the long-term benefits of investing in quality public structure

As we pointed out four years ago, there is no such thing as a free lunch. If you want tax cuts, you need to pay for them. There is no voodoo economics, tax cuts do not pay for themselves. Unlike the federal government that can run deficits, the state must rely on the revenue it receives each year to make the important investments we need to make West Virginia a better place to raise a family and conduct business. When you deprive the state of revenue – like depriving you car of gas – it cannot run effectively and the places you want to go become further and further out of reach.

At the very least, what the above highlights is that the Governor and Legislature should take a balanced approach to reducing the FY 2014 budget deficit. It should include a combination of cuts and revenue increases. Our children’s future depend on a strong and healthy budget. Let’s make sure we don’t take that away.