Last night the Charleston Area Alliance hosted a discussion between Senator Brooks McCabe, PEIA director Ted Cheatham, and yours truly on how to address the state’s growing OPEB (other post-employment benefits) liability. As readers may know, we published a detailed report on how the state should handle this problem back in January. I do not have much more to add to the discussion that was not in our report, but uploaded here are some of my notes from the event.

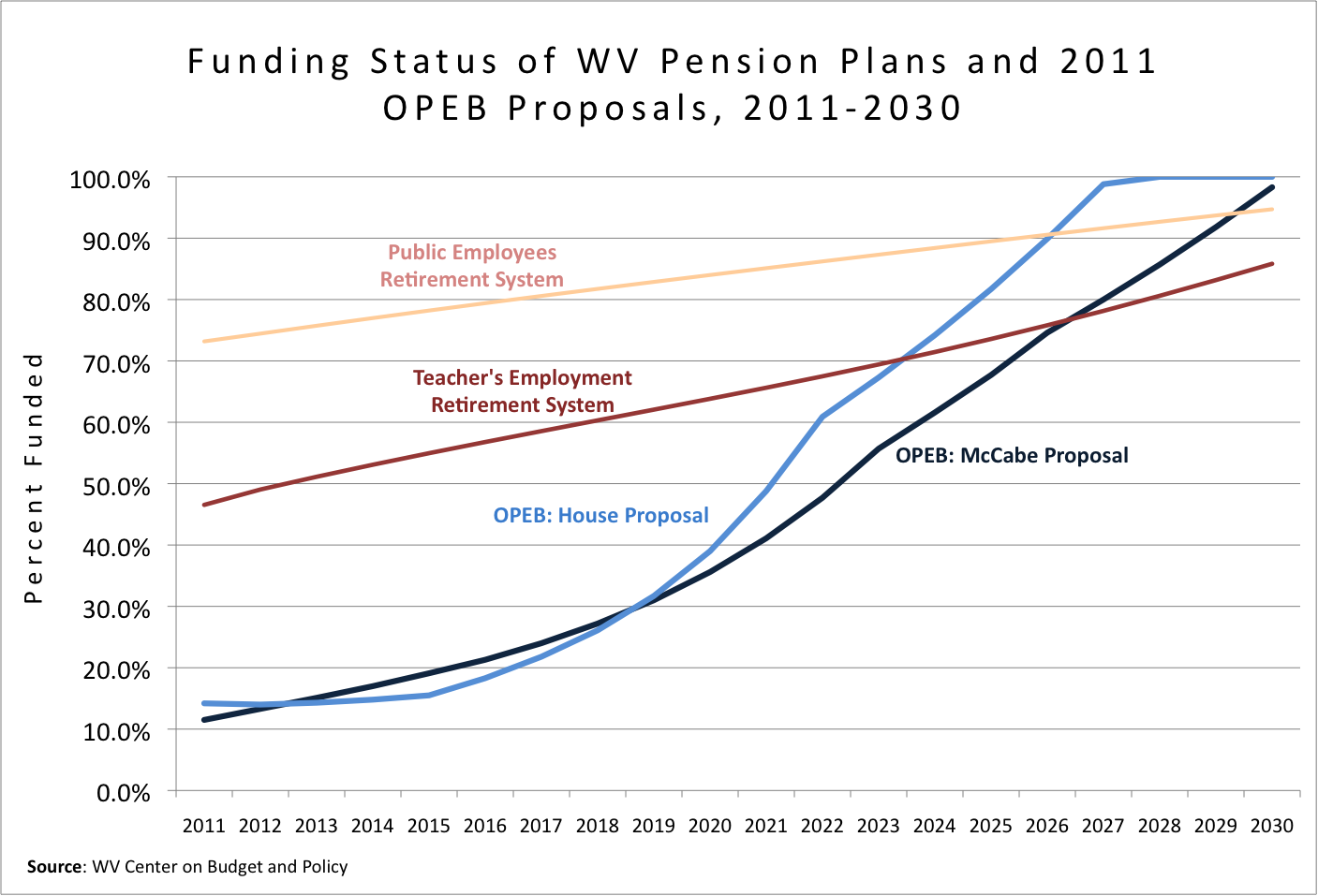

One thing that I stressed at the event was that the state should not overreact to the OPEB liability by completely pre-funding it. As the chart below shows, both the House and Senate legislation would fully fund the OPEB liability by FY 2028 and FY 2030 respectively, while our two biggest pension plans would only have a funding ratio between 80-95 percent.

So, why shouldn’t we fully pre-fund the OPEB liability? Although it seems counter intuitive, there are several good reasons.

First, unlike pensions which are a legal and moral obligation of the state, retiree health care is not. The PEIA board can take it away tomorrow with little recourse (no collective bargaining) from public employees. Therefore, it makes little sense to fund the OPEB liability at a higher rate than our state’s pension liability. Secondly, many experts argue that 80 percent funding is sufficient for public pensions because states and localities, as ongoing entities, can use tax revenues to make up a shortfall if necessary. Here is what a recent GAO report said:

“Many experts and officials to whom we spoke consider a funded ratio of 80 percent to be sufficient for public plans for a couple of reasons. First, it is unlikely that public entities will go bankrupt as can happen with private sector employers, and state and local governments can spread the costs of unfunded liabilities over up to 30 years under current GASB standards. In addition, several commented that it can be politically unwise for a plan to be overfunded; that is, to have a funded ratio over 100 percent. The contributions made to funds with excess’ assets can become a target for lawmakers with other priorities or for those wishing to increase retiree benefits.”

Instead of aiming for 100 percent funding by FY 2030, the state should aim for 60 to 80 percent funding by FY 2040. This will put us way ahead of most states and will also free up millions of dollars that can go toward many of the state’s more pressing economic problems, such as having the least educated (formally) workforce in the country.

Lastly, to paraphrase Donald Rumsfeld, there are a lot of known unknowns regarding the Affordable Care Act. For example, the ACA provides subsidies up to 400 percent of the federal poverty level for individuals and families who purchase insurance in the health exchange. It is possible that some public workers – especially those that perform physically demanding work – will have to retire before they reach age 65. Therefore, they could receive a better deal by purchasing health coverage in the exchange than taking the retiree health subsidy provided by PEIA.

For example, the average early retiree (age 55-64) pays about $252 a month or $3,024 annually toward his or her PEIA health insurance. Based on the Consolidated Retirement Board Calculator, he or she would have an annual annuity of $25,000 based on a final salary of $50,000. Assuming no other sources of income, he or she would be eligible for a health exchange subsidy at 250 percent of the federal poverty level ($27,075 for a single person in 2010) and pay $2,315 or about $700 less than PEIA.

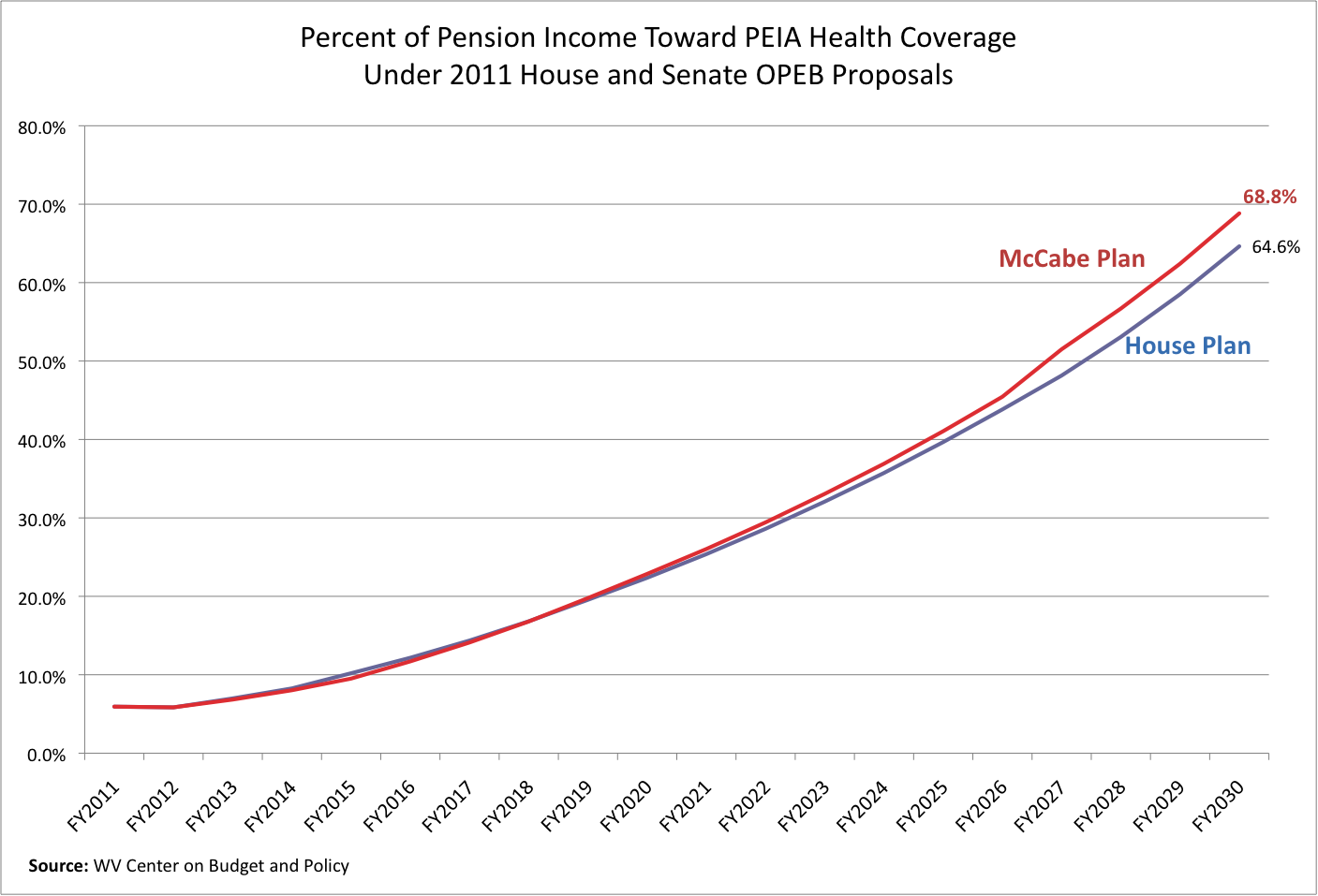

Currently, between 30 to 40 percent of retiree health care costs are non-Medicare retirees in PEIA. If our state proceeds with a strong exchange and the ACA remains intact, it might be better to phase out the retiree health subsidy for early retirees instead of capping the amount for all retirees. This could drastically reduce the OPEB liability without harming most retirees. As the table below shows, both the House and Senate plan (McCabe plan)) would require that retirees pay on average between 65 and 69 percent of their pension income toward purchasing health insurance in FY 2030 compared to less than 10 percent today.

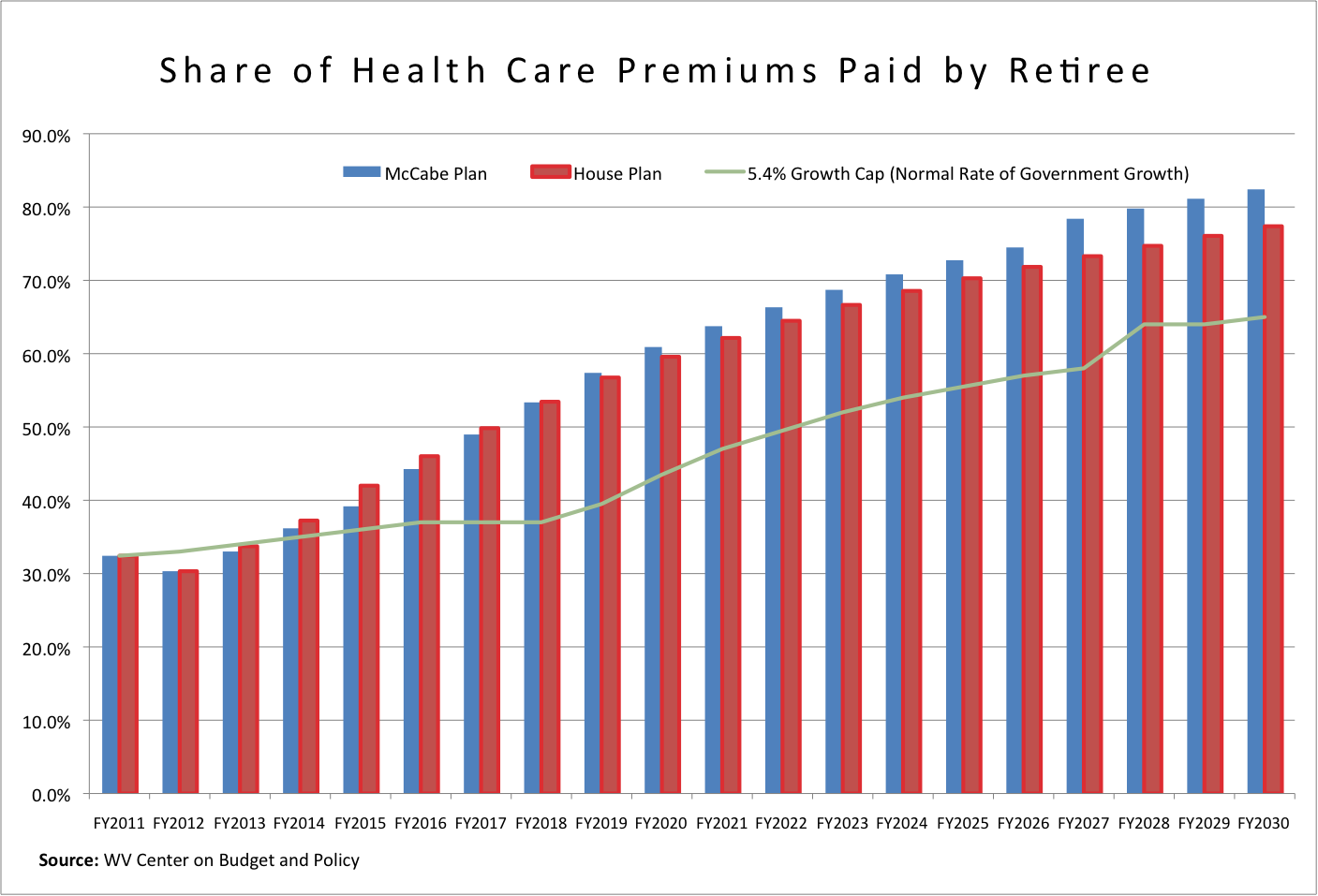

The table below highlights the share of health care premiums that retirees would pay under both the House and Senate (McCabe Plan) bills. As you can see, retirees would have to pay on average about 80 percent of their health care premiums – which would effectively end the retiree benefit. If the state decided to cap the retiree subsidy to the normal rate of government growth instead of arbitrarily capping the subsidy, it would provide more of a benefit to retirees while not crowding out other government spending.

Given the fragile nature of the OPEB liability and the possibilities regarding health care reform, it makes much more sense to take a more judicious approach to solving the OPEB problem. As shown above, there are solutions to addressing the OPEB liability that do not require drastically reducing health care benefits for retirees or hurting our state’s ability to make the important public investments it needs to make in educating our workforce.