Last week, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced that states could remove some low-income adults from receiving Medicaid coverage if they are not working more than part-time or participating in work-related activities. This is a sharp departure from prior administrations that have rejected so-called “work requirement” waivers from states because it doesn’t align with the objectives of the Medicaid program.

As noted in previous blog posts, West Virginia’s DHHR plans to submit a waiver (under Section 1115 of the Social Security Act) in 2018 asking CMS to modify its Medicaid program so if can implement work requirements for the Medicaid expansion population.

So far, eight states have submitted waivers to implement work requirements – including our neighboring state of Kentucky. The WV DHHR have said they want to align the proposed work requirements with the state’s SNAP program, which is what the state of Kentucky hopes to do. Currently, unemployed childless adults between the ages of 18 and 49 must work or participate in an approved education activity for at least 20 hours per week (80 per month) to qualify for SNAP in nine West Virginia counties. DHHR exempts those that: a) participate in a drug addiction or alcohol treatment or rehabilitation program; b) are caring for an incapacitated adult; c) are medically certified as unfit to work; or d) are at least a part-time student.

State proposals vary as to what is considered as work-related activities, the age of beneficiaries that the work requirements would apply to, and exemptions to work requirements (e.g. pregnant women, chronically homeless, etc.). Some states also require childless non-disabled adults on Medicaid to verify their income and work requirement on a monthly basis and are placing lifetime limits (e.g. 5 years) on Medicaid enrollment. Meanwhile, some states have included other eligibility and enrollment restrictions in their Medicaid waivers to cover traditional Medicaid populations, including asset tests, lockouts for failure to timely renew eligibility, premiums and copays, and drug testing.

Work Requirements Would Result in Decreased Enrollment

As discussed previously, applying these types of restrictions to West Virginia’s Medicaid expansion population will lead to thousands of West Virginians being kicked off of Medicaid. In fact, just the paperwork alone is likely to reduce enrollment in Medicaid. The state of Kentucky estimates that if its work requirement is implemented that it would lead to nearly 100,000 Kentuckians losing Medicaid coverage in five years. Currently, there are about 650,000 adults enrolled in Medicaid in Kentucky. If this percentage (15 percent) is applied to West Virginia’s adult Medicaid expansion population, approximately 24,000 low-income adults could lose Medicaid coverage if the state adopts a work requirement similar to Kentucky.

Most Medicaid Beneficiaries Who Can Work, Do Work

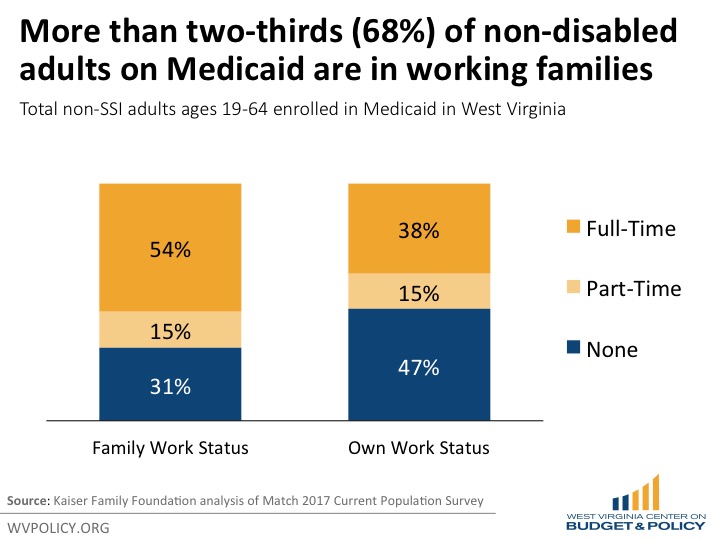

Nearly seven in 10 adults who aren’t disabled live in working families in West Virginia, while most (53 percent) are working themselves, according to estimates from the Kaiser Family Foundation. The vast majority of those who aren’t working in West Virginia have an illness or disability (41 percent), are caring for a family member (34 percent), or are in school (12 percent). Approximately 8 percent cannot find work and 4 percent are retired.

A substantial body of evidence shows that work requirements do not promote long-term employment, reduce poverty, or lead to improved health outcomes. Instead of boosting work, Medicaid work requirements do little to nothing to expand employment. If West Virginia is interested in helping support work with a waiver, it could follow the lead of Washington State to expand services to that help beneficiaries with physical or behavioral health conditions gain access to housing and employment.

One of the central reasons why West Virginia struggles with chronic poverty and lags behind other states in economic growth is the poor health of the state’s population and its ultra-low post secondary educational attainment. Instead of taking health coverage away from thousand of West Virginians with a work requirement, the state could raise its minimum wage, enact a refundable earned income tax credit, and make investments in public colleges that improve the quality of the education while making it more affordable.