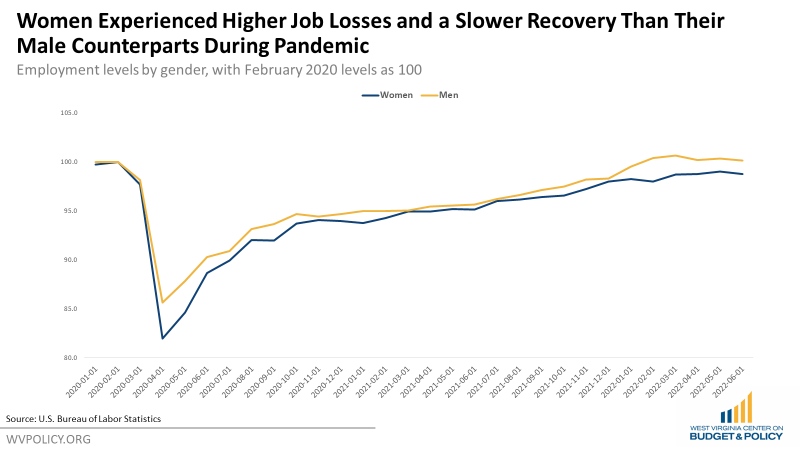

While it has been nearly two and a half years since the COVID-19 pandemic began, women have still yet to return to their pre-pandemic employment levels, down 900,000 jobs in June 2022 compared with February 2020. Over the same period, men have reached and now exceeded their pre-pandemic employment levels. Women also saw larger total job losses than men at the peak of the pandemic. While the deeper and longer-lasting job loss impacts of the pandemic on women are likely due to a number of factors – most importantly the disproportionate share of caregiving that women shoulder – there will likely be lasting work impacts for women even when jobs are fully recovered. Policymakers would do well to focus on the existing holes in caregiving that the pandemic magnified and address newly emerging challenges to women and family wellbeing.

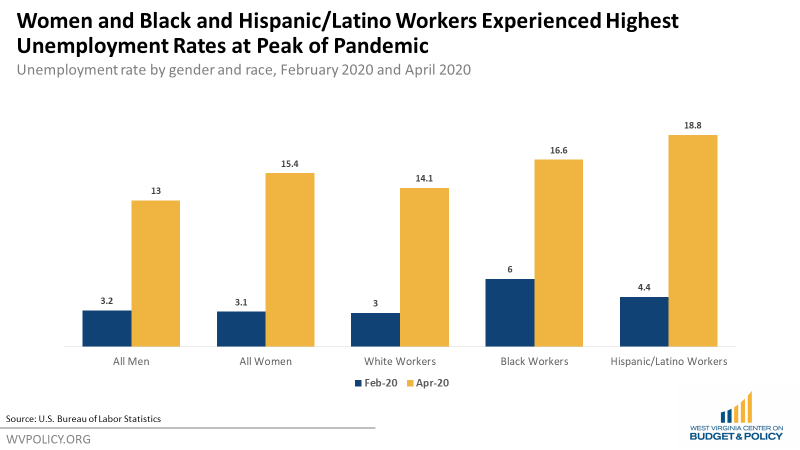

At the height of the pandemic’s job losses, women lost 13.5 million jobs nationally, higher total job losses than their male counterparts. This was in part due to job losses being concentrated in industries that employ more women like education, hospitality, and health care services. Despite having nearly identical unemployment rates prior to the pandemic in February 2020 (3.2 percent vs. 3.1 percent) men’s unemployment rate peaked at 13 percent in April 2020 while women’s unemployment reached 15.4 percent. Racial disparities also emerged, with Black unemployment spiking to 16.6 percent and Hispanic/Latino unemployment at 18.8 percent compared with 14.1 percent white unemployment.

In addition to deeper job losses at the height of the pandemic women also faced a slower jobs recovery, as evidenced by the remaining 900,000 job gap for women, while men have now exceeded pre-pandemic employment levels. Much of this remaining gap is attributed to women shouldering most of the caregiving responsibilities in our society. In 2021, prime-age women were six times more likely than men to report not working due to child care issues and twice as likely to not be working due to other family obligations besides child care.

While West Virginia-specific data on employment by gender through the pandemic is not yet available, total state employment is still down 10,400 jobs compared with February 2020 through May 2022. It is likely that some of those “missing workers” who are not accounted for by West Virginia’s population decline are women who are still facing caregiving challenges. Moreover, caregiving responsibilities kept some women out of the workforce long before COVID-19, a long-standing issue that was exacerbated during the pandemic.

Looking ahead, the job loss impacts of the pandemic may continue to impact women for years to come. In addition to economic insecurity, periods of joblessness – more likely to have impacted women than men over this period – have negative impacts on wage growth and promotions. Additionally, resume gaps can impact one’s ability to be competitive for new jobs. One study found that women who are working feel less comfortable asking for raises or promotions than they did pre-pandemic. All of these challenges could have ongoing impacts on women’s earnings and family economic security.

Several state-level policies should be considered to address the challenges that women have faced in reaching their pre-pandemic employment levels and ensure that they do not fall behind their male counterparts in job opportunities and wage growth. First and foremost, the state should invest more funding in child care subsidies and child care provider infrastructure, which would grow the child care workforce and allow more parents to work in other industries. West Virginia lawmakers could use a portion of the FY 2022 surplus or American Rescue Plan Act funds to improve its child care system. Policies like paid family and medical leave and fair scheduling policies would also target some of the specific barriers that those with caregiving responsibilities face by ensuring that workers have paid, job-protected time off to care for a new child or seriously ill family member, as well as advanced notice of work schedules to better balance caregiving responsibilities.

Additionally, taking steps to close the gender pay gap would help address the pandemic’s negative impact on women’s wage growth and job opportunities. Some tangible policies include strengthening salary transparency laws and prohibiting employers from asking prospective candidates about their salary histories. Both of these policies would help ensure women are paid a fair market salary rather than being punished for having a resume gap or being paid unfairly at a prior job.