Last week, I was asked to present before the Senate Economic Development Committee on our projected estimates regarding S.B. 182 – which creates the WV Future Fund proposed by Senate President Jeff Kessler.

During the meeting, Mark Muchow, the Deputy Secretary of the WV Department of Revenue, also presented the committee with a history of the WV severance tax. At the end of his presentation, Muchow also compared the mining (oil, natural gas, and coal) gross domestic product of Wyoming and West Virginia, showing that Wyoming’s natural resource economy was about twice the size of West Virginia. In response to questions about the taxation of minerals in Wyoming and West Virginia, Muchow also told legislators that West Virginia taxes mineral property while Wyoming does not.

After doing a little research after the meeting, I discovered that Muchow failed to mention that Wyoming does levy a county gross products tax based on the taxable value of minerals produced in the county. According to the Wyoming Department of Revenue, this ad valorem property tax brought in over $1.2 billion dollars in revenue for Wyoming county governments in 2009 based on 2008 taxable mineral production values. Of the $1.2 billion, approximately $967 million was from coal and natural gas. According to two reports conducted by West Virginia University on the economic impact of the natural gas and coal industry in the state, total West Virginia property tax revenue in 2008 for coal was $90.8 million and $58.3 million for natural gas – a total of $149.1 million. According to these estimates, West Virginia collected about 15.4 percent of the amount in natural gas and coal property taxes that Wyoming collected in 2009.

Upon doing this research, I remembered that Marshall University’s Center for Business and Economic Research conducted two studies surveying the taxation of coal (2010) and natural gas (2011) in the country. After reading the sections of both studies that discussed how Wyoming taxed coal (pg. 26-27) and natural gas (pg.71-72), I discovered that neither of them mentioned Wyoming’s country gross products tax in their analysis. And this is a big deal. Why? Because, in general, the county gross products tax brings in about the same amount of revenue as the state’s severance tax on coal (7%) and natural (6%).

To make sure I was correct, I looked at the citation in the coal taxation report and it sourced an interview with Craig Grenick of Wyoming’s Department of Revenue. So, I contacted Mr. Grenvik and he confirmed that the Marshall studies both failed to mention the county gross products tax in their surveys of coal and natural gas taxation. I thought this was interesting, considering that the principal author of both of these studies, Cal Kent, has repeatedly questioned our studies over the last two years. For example, just recently Mr. Kent presented this report on the taxation of natural gas in response to our report during legislative interims in November. This report also failed to mention the Wyoming county gross products tax.

With this in mind, Sean and I put together a chart (see below) showing the effective property and severance tax rates for coal and natural gas in Wyoming and West Virginia in 2008. As you can see, the overall effective property and severance tax rate on coal and natural gas in Wyoming is 9.3%, compared to 5.8% in West Virginia.

Sources: Wyoming Department of Revenue 2009 Annual Report, EIA Annual Coal Report 2010, EIA natural gas wellhead value and marketed production 2008, West Virginia Tax Department severance tax disaggregation, WVU BBER The West Virginia Coal Economy 2008, WVU BBER The Economic Impact of the Natural Gas Industry and the Marcellus Shale Development in West Virginia in 2009.

So what if West Virginia taxed coal and natural gas property at the same rates as Wyoming? The property tax would have produced $566 million instead of $149 million, a difference of $415 million – which is actually more than what was collected in state coal and natural gas severance taxes in 2008.

In addition to leaving out the property tax in Wyoming, the CBER and Mr. Kent are also guilty of overestimating the effective rate of the severance tax on natural gas in West Virginia. In the above chart, we note that production value for natural gas in West Virginia is not available, and instead we treat the statutory rate as the effective rate to derive at total production value. Mr. Kent ran into this same problem in this report about the severance tax. On page 6, CBER uses the national average price of gas to derive an effective rate for West Virginia, which comes out to 7.83%. But this is actually higher than the statutory rate, which should never happen, since the deductions and exemptions lower the effective rate below the statutory rate.

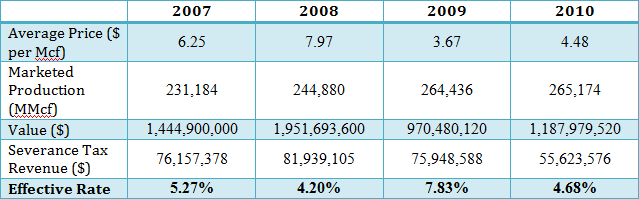

How did this happen? The price of gas has been on a roller-coaster ride the past few years, and fell dramatically between 2008 and 2009. But these average prices are calculated by calendar year, while the total severance tax revenue used in the calculation was collected in a fiscal year. When the price ch

anges so dramatically in a calendar year, the use of a fiscal year’s revenue to calculate the effective rate distorts the results. And as the table below shows, 2009 happened to be a year when this distortion was the greatest, and is quite an outlier compared to other available years.

Sources: EIA and WV State Tax Department

The CBER report concluded that West Virginia’s natural gas severance tax was the 4th highest of the 15 states examined, based on 2009’s flawed effective rate calculation, and higher than Wyoming, Alaska, Kentucky, and Texas. But if 2010’s effective rate was used instead, then West Virgina ranks 10th highest, and lower than all of those energy states. However, as page 3 of the CBER report shows, several different calendar and fiscal years were used to compare severance tax revenue between states, making all of the effective rates in the report suspect.

These issues raise the question of what else Mr. Kent has left out or misrepresented in his reports to the legislature over the years. In the debate over the taxation of the coal and natural gas industries, as well as in the debate over the creation of a permanent mineral trust fund, both state officials and Mr. Kent have presented the legislature with incomplete, misleading, and often inaccurate information. These issues highlight the need for an independent and professional fiscal office to inform the public debate over these and other important issues with all of the facts and available evidence.

The above analysis also clearly shows that West Virginia’s mineral property and severance taxes are not out of line with a conservative state like Wyoming and not a barrier to creating a permanent mineral trust fund. Our only barrier seems to be that we are not doing as good a job as Wyoming in ensuring that our state benefits from its rich natural resources.

Ted Boettner

Sean O’Leary