This week, the West Virginia legislature originated a bill in the House Finance Committee to enact work requirements for Medicaid. The bill quickly passed the committee and headed to the House floor. The bill stems from actions last year, when the Trump administration announced that it would allow states to remove some low-income adults from receiving Medicaid coverage if they are not working more than part-time or participating in work-related activities. This is a sharp departure from prior administrations that have rejected so-called “work requirement” waivers from states because it doesn’t align with the objectives of the Medicaid program.

As one of the poorest states in the nation, with some of the highest rates of illness and disability, Medicaid is one of the most important programs benefiting West Virginia. Almost a third of West Virginians are covered by Medicaid, with most of the cost paid by the federal government, while since the expansion of Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act the number of uninsured West Virginians has plummeted. Medicaid expansion has also been shown to improve health outcomes and access to preventive services. Imposing a work requirement would be taking the state backwards, resulting in fewer people having healthcare coverage, while increasing financial insecurity and debt.

The push to add a work requirement to Medicaid is largely based on the myth that people covered by Medicaid are not working, or would be encouraged to increase their work by the requirement, with the goal of having their incomes rise above the level that makes them eligible for Medicaid. However, this assumption ignores both the realities of West Virginia’s Medicaid population, low-wage work, and barriers to employment.

According to data from the 2017 Current Population Survey, 44 percent of non-disabled (not receiving SSI) adult Medicaid recipients in West Virginia are working, while another 7 percent are unemployed but looking for work. According to WV DHHR, 66 percent of adult and child Medicaid enrollees in West Virginia are in families with a worker. Of those adult West Virginia Medicaid recipients who are not working, most are ill or disabled, taking care of family, in school, or retired.

Work requirements also ignore the nature of low-income work. For example, the work requirement sought by Kentucky in its 1115 waiver would require Medicaid recipients to work at least 20 hours per week. In fact, according to 2016 Census data, 10 percent of non-elderly West Virginia adults whose incomes qualify them for Medicaid work less than 20 hours per week. As of 2016, the industries that employed the most Medicaid expansion-eligible adults in West Virginia were restaurants and other food services, construction, and department and discount stores, all of which often provide only part time and sometimes irregular work opportunities.

Evidence has shown that work requirements in other federal assistance programs have failed to promote long-term employment. A review of the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program showed that work requirements only resulted in a short-term increase in employment, but employment outcomes faded after two years and the requirement didn’t have any effect on employment five years afterward. Those who are subject to work requirements typically land in entry-level, low paying jobs. Few have transitioned to better-paying jobs over time, and most continue to struggle with meeting basic needs.

West Virginia’s own experiment with work requirements for SNAP was largely a failure. Only 259 people out of 14,000 referrals found employment, while food pantries saw a sharp increase in meals provided.

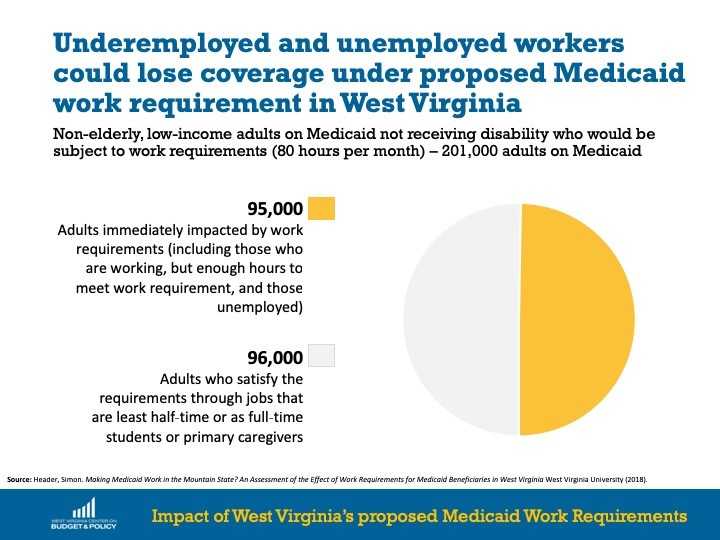

A study done by Simon Haeder, a professor at WVU, found that about 200,000 Medicaid beneficiaries, ages 18-64, would be subject to work requirements in West Virginia. Over half are people who already satisfy the requirements through jobs that are at least half-time or as full-time students or primary caregivers.The remaining 95,000 people would be immediately impacted by the work requirements. These include 78,000 who are unemployed and 17,000 who are working part-time, but not enough hours to comply with the requirements. These people would face significant barriers to employment. Among the 78,000 beneficiaries who are currently unemployed, nearly three quarters (72 percent) experience one or more barriers, including the following:

Finding jobs, paid or volunteer, for 95,000 unemployed and underemployed beneficiaries would be daunting. Many counties have consistently high rates of unemployment. Thirty-three of the state’s 55 counties are in Labor Surplus Areas, defined by the U.S. Department of Labor as having an annual unemployment rate at least 20 percent higher than the national average.

While the unemployed and underemployed beneficiaries would be at major risk of losing coverage. who meet the work requirements can still lose their Medicaid coverage over paperwork. Researchers estimate that about 80 percent of the people who lose their coverage will be individuals who met the requirements, but did not submit documentation of their hours worked or their exemptions.

The bill states that factors such as education, community engagement and work contribute to individual’s health and wellness. While that may be true, taking away medical coverage runs contrary to those goals. Taking away medical coverage makes it harder to get healthy, harder to alleviate poverty, and harder to transition into stable work environments. Experts agree almost univeraly that sustained health coverage has a strong, positive effect on supporting work efforts. This bill moves in the opposite direction.

Instead of enacting misguided and harmful work requirements, West Virginia should be looking for ways to expand health care coverage even further. This could include strengthening the state insurance market by implementing a state-based individual mandate, establishing a reinsurance program, restricting short-term, limited duration health plans, and expanding the Children’s Health Insurance Program and a dedicated outreach and enrollment campaign during open enrollment for the Affordable Care Act’s marketplace.

One such option is already on the table at the legislature. Expanding Medicaid eligibility for pregnant mothers, SB 564 has been introduced and has passed the Senate Health Committee. But while SB 564 was double referenced and is moving slowly through committee, the work requirements bill was originated in committee, passed out that same afternoon, and is already on first reading on the House Floor. West Virginia can do better.