Picture this: there is a federal program that is able to help with transitioning drug offenders back into society when they are released from prison. It provides up to around $200 per month (non-cash) only to be used to meet necessary food expenses for the offender and their family. It is paid for with federal dollars and would have little to no added administrative cost because it’s already in place through existing West Virginia programs. Would you be interested?

This program actually exists. The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, is a federal program that reduces food insecurity by distributing funds to low-income families that help them buy groceries. The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) defines food insecurity as the lack of consistent access to enough food for a healthy life. In 2017, more than 42 million people nationwide received benefits through SNAP, giving them access to food for themselves and their families.

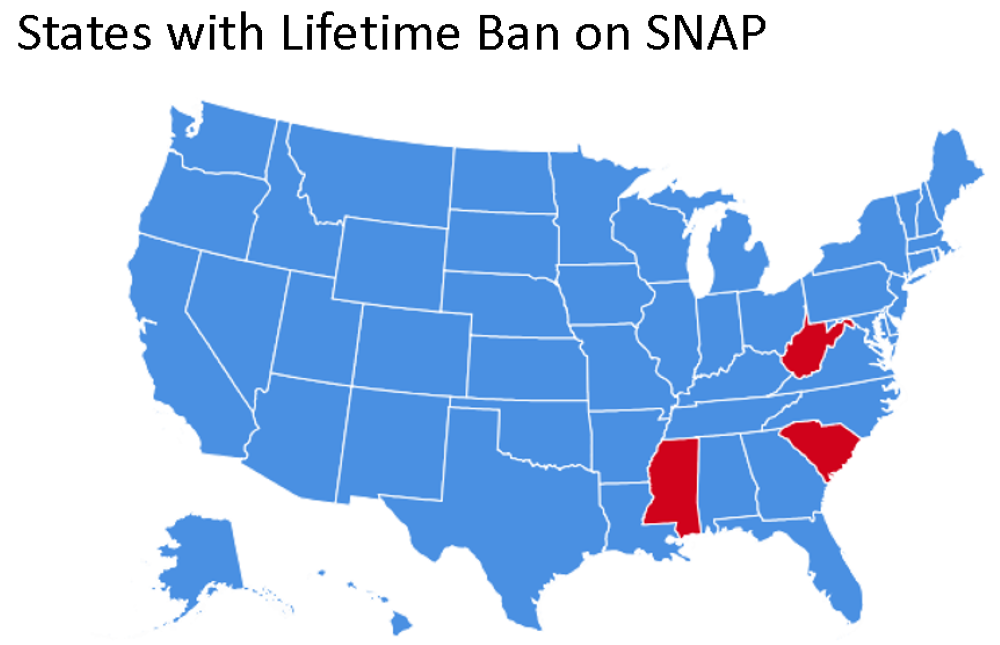

Under federal law, however, if a person has a felony drug conviction, they are banned from receiving any SNAP benefits—for life. The ban on SNAP for drug felons was part of the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA) and doesn’t apply to any other type of felony. While the ban is a federal law, there is a provision that allows states to opt out or modify the ban. Since 1996, most states have recognized the ban’s unfairness and opted out completely or adopted modified restrictions. Today, just West Virginia and two other states—Mississippi and South Carolina—still have a full lifetime ban on SNAP for those convicted of drug felonies.

In 2016, over 2,100 drug felons were denied SNAP benefits in West Virginia. This figure doesn’t count the number of people who didn’t even bother applying because they knew they would be denied. There is no benefit to the state in not allowing an individual with a drug felony to receive SNAP. Since it’s a federally funded program, allowing a drug felon to receive SNAP wouldn’t burden the state budget and it also doesn’t produce any savings. In fact, the ban added up to over $3.1 million in missed federal funds for West Virginia in 2016 alone. Not only did the state miss out on federal funds, but also much-needed economic activity. Every dollar received through SNAP benefits results in about $1.80 in economic activity—meaning the Mountain State could have potentially seen around an added $5.7 million in economic activity just by allowing these 2,100 to receive SNAP in 2016.

If the ban doesn’t benefit the state, it certainly doesn’t benefit the individuals who are impacted by it. People who are formerly incarcerated have a difficult enough time trying to successfully re-enter society and depriving them of food isn’t going to help. One study shows that around 91 percent of people recently released from incarceration experience food insecurity, and 37 percent of those people didn’t eat for an entire day in the past month. When people with drug convictions are denied SNAP benefits, it only makes getting back on their feet even harder.

Not only does this impact the person who is directly experiencing it, but denial of SNAP to ex-drug felons also impacts their abilities to feed their families. SNAP is calculated by household, not individual—this means a household of four people receives benefits calculated for four people. But, if one of those people happens to have a drug felony on their record, SNAP doesn’t consider that person when benefits are distributed. In a situation like this, a family of four would only receive benefits for three people. This family would be forced to readjust the amount of food they eat to account for the person not able to receive benefits. To make matters worse, if the individual with a drug felony has a job and contributes to the household’s income, that income would actually decrease the amount of SNAP benefits the family is eligible to receive. Denying people SNAP benefits has the potential result of forcing people choose between trying to make money to support their family or making no money so the family can maximize what SNAP benefits they do get. It also could make it much more likely that the person could return to drug use or rely on criminal activity in order to get money for food.

The more than 2,100 people unable to get SNAP aren’t just numbers to keep track of—they’re people with names, families, and stories. Natisha from Jackson County says:

“I can’t pay my (court) fees off because I have to pay for my own food, housing and other needs I have. I have health problems as well and have lived in total filth because I could not afford a decent place to live. That is another reason my addiction spiraled out of control. This ban has really affected my addiction. I use meth because I can’t afford to eat. I was also stealing food to be able to survive.”

SNAP is vital part of rehabilitation for many people. Junie from Clendenin says:

“I am in recovery for heroin addiction and I have three children. As a child myself my parents were drug addicts. If it weren’t for being able to receive food stamps my parents would not have been able to provide for my brother and I.”

For parents who are in recovery and trying their best to piece their lives back together, the last thing they need is facing barriers to feed themselves and their children.

The SNAP ban doesn’t affect all people with drug-related felonies equally. Because of racial disparities in the criminal justice system, the SNAP ban disproportionately impacts people of color. Despite using drugs at roughly the same rate, black people are four times as likely than whites to be arrested for drug offenses and 2.5 times as likely to be arrested for drug possession. In addition to race, gender also affects those hardest hit by the SNAP ban. The majority of SNAP recipients are women, who are more than twice as likely as men to receive SNAP benefits at some point in their lives. Women are also more likely to be incarcerated because of a drug-related conviction. In 2015, a quarter (25 percent) of women serving time in state prison had been convicted of a drug offense compared to 14 percent of men. Due to racial disparities, women of color may be particularly impacted by the SNAP ban. The imprisonment rate for Black women (97 per 100,000) was nearly twice the imprisonment rate for white women (49 per 100,000).

The good news is there are moves in the West Virginia legislature to lift this ban. HB 2459, sponsored by House Judiciary Chair Shott, passed overwhelmingly (98-0) and would opt the state out of the lifetime SNAP ban for drug felons. The Senate companion bill, SB 394, which would exempt West Virginia from the federal statute, has strong bipartisan support.

Everyone deserves to eat—even those who have made mistakes in their past. Access to SNAP can be an important part of helping individuals successfully re-enter society since it provides basic food assistance to those without adequate income. Studies suggest that full eligibility for SNAP may reduce the risk of recidivism for those recently released from incarceration.The formerly incarcerated already face barriers to employment upon release—they shouldn’t have to struggle to get food on top of everything else. It is necessary for the Mountain State to lift the SNAP ban on drug felons and offer them support rather than kick them when they’re already down.