According to a study by the National Commission on COVID-19 and Criminal Justice, the COVID-19 mortality rate nationwide is twice as high in prisons compared to the general population. Social distancing is difficult if not impossible in correctional facilities due to their congregate nature. This, combined with the reality that incarcerated people are more likely to have chronic health conditions such as diabetes and high blood pressure, underscores why it was crucial for corrections agencies around the country to rapidly decarcerate in order to mitigate harm done to the health and well-being of those inside (or who would have otherwise been inside if it were not for decarceration).

West Virginia responded quickly, reducing its prison population by nearly 1,000 people between March 2 and July 2. But with an ongoing pandemic and one of the country’s worst transmission rates, a looming housing crisis, high rates of food insecurity, and a dismal employment landscape, successful reentry requires that the state provide more support for its returning citizens, both during the pandemic and long after.

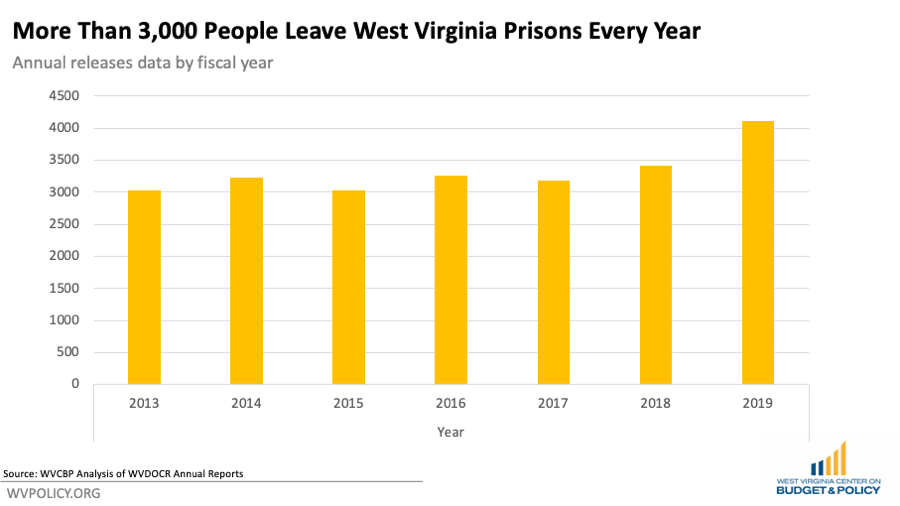

At least 95 percent of all state prisoners in the United States are eventually released, and re-entry into society is nearly always a disorienting process. In West Virginia, more than 3,000 people leave state prisons every year, whether through parole or because their sentences are completed. When it comes to the state’s jails, 40,000 people are discharged every year.

West Virginia’s 3-year recidivism rate is 28 percent, meaning that more than one in four people released from prison are rearrested within 3 years.

Recidivism and reentry are understudied, but what is clear is that factors such as employment, housing, education, mental health, substance abuse treatment, and housing all influence the likelihood of whether someone will succeed after returning home from prison. Even something seemingly simple such as being able to obtain a government identification in order to become employed or enroll in social services can be a roadblock for formerly incarcerated people. Fortunately, thanks to a law enacted in 2019, West Virginia does provide a temporary photo identification for people who are being discharged from prison.

In a piece at the beginning of the pandemic, The Council of State Governments Justice Center outlined a set of key questions that stakeholders in the criminal justice system should consider as they grant incarcerated people early release. Thinking critically about these questions and others should be part of a cohesive strategy to protect the health of formerly incarcerated individuals and their communities, as well as set them up with the strongest chance of success post-release.

The questions include:

1. Are there procedures in place in advance of release to ensure that the person is free of COVID-19, and are they implemented in a timely manner to avoid delayed release?

2. Does the person have the basic supplies they need—food, hand sanitizer, etc.—to ensure they remain healthy once they’re home?

3. Does the person have a safe home to return to that is also virus-free? If not, what alternative community-based housing options may be utilized?

4. What medical or behavioral health medications and services does the person require immediately and potentially during a two-week quarantine? Do arrangements need to be made for them to access some of those services virtually?

5. Have we prepared the person with the technological literacy and equipment to receive and benefit from virtual, rather than in-person, supports?

6. If the person is being released to parole or other supervision, how are we asking them to interact with their parole officer in a time of social distancing?

7. If the local economy has collapsed, are we providing the person with access to public benefits to support themselves and their loved ones?

Reentry stakeholders say that West Virginia corrections officials have stepped up and addressed some of these unique concerns. For example, incarcerated people are quarantined for the two weeks prior to their release to reduce their risk of being exposed to COVID-19. With that said, certain aspects of the reentry process remain out of the purview of corrections employees. To ensure that people being released from prison have adequate support as they navigate employment, social services enrollment, and searching for housing, policymakers, community leaders, corrections staff, and other stakeholders must work together.

Policymakers at both the local and state levels should prioritize the needs of returning citizens and invest in solutions that will help them as they reacclimate to their communities. This is important to focus on now more than ever as the pandemic continues to disrupt our lives. In the coming months WVCBP will be working with partner groups to identify and research barriers and challenges confronting returning citizens in West Virginia and offer policy recommendations and solutions to strengthen supports for those leaving the justice system.