Last week, the Bureau of Labor Statistics released the April jobs report, showing that job growth slowed significantly in April and raising concerns about the economy.

Following these disappointing jobs numbers were anecdotes from businesses claiming to struggle to find workers willing to work, particularly in the restaurant industry. “Generous” unemployment benefits were quickly blamed, with the argument that with the enhanced $300 week in unemployment benefits from the CARES ACT/American Rescue Plan, too many workers were content to collect unemployment rather than go back to work, creating a “labor shortage” where “demand for workers is greater than the supply of those willing to get back into the labor force.” However, the economic data shows that while there are some signs of tightness in the labor market, there are still more job seekers than jobs available, and the economy is adjusting after the huge shock caused by a global pandemic.

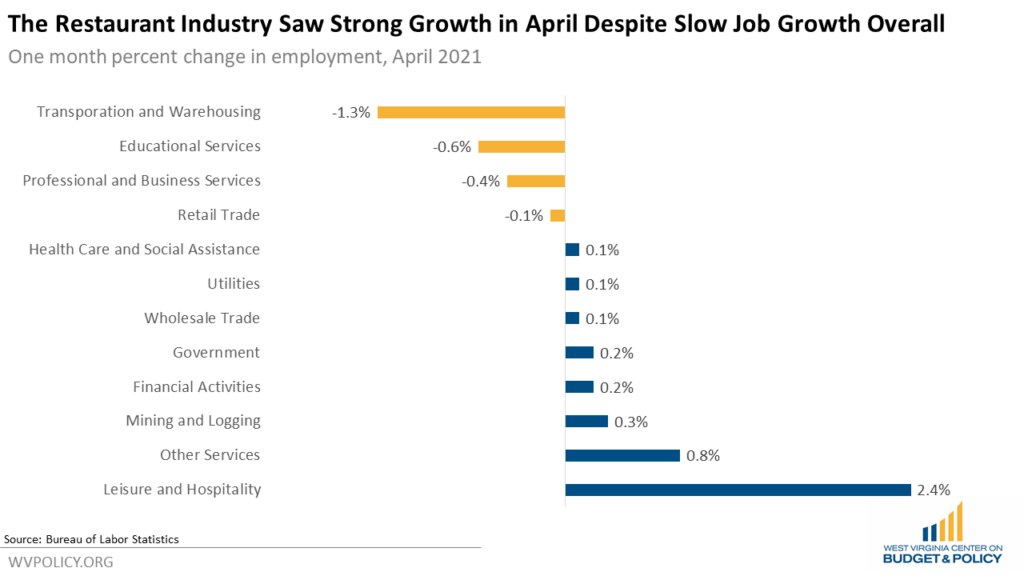

First, while the April jobs numbers were disappointing overall, the restaurant industry was stronger than in any other sector. Other low-wage industries — where unemployment benefits replace a higher share of wages — also showed faster growth than high-wage industries. This is the opposite of what would happen if unemployment benefits were keeping people from working.

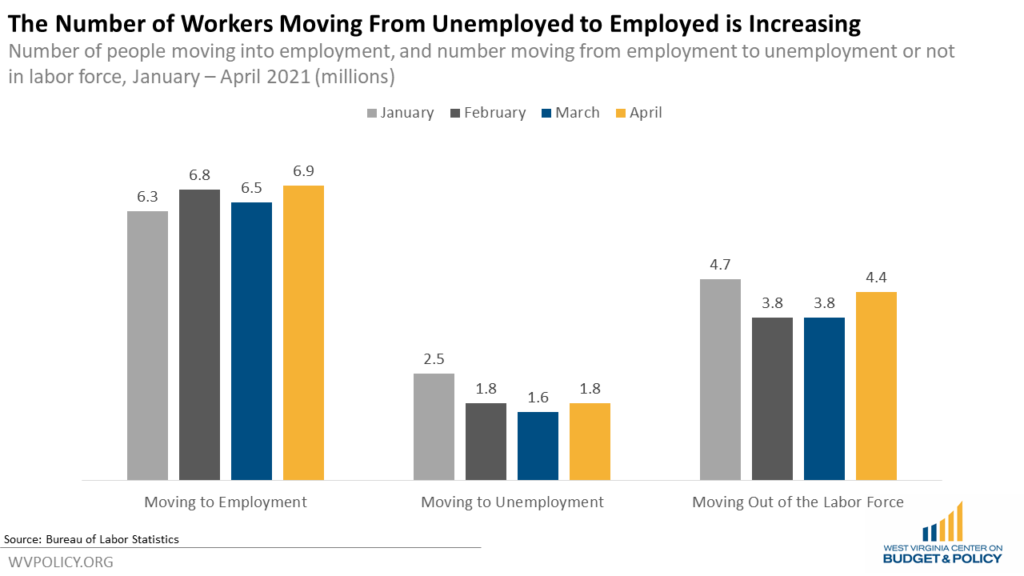

The jobs flow data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, which show how many people moved from unemployed to employed and vice versa — rather than just the net employment increase — also disputes the idea that unemployment benefits are holding back job growth.

In April, 6.9 million people were newly employed, up from 6.5 million in March. More unemployed workers are finding jobs than before — again, the opposite of what would be happening if overly generous unemployment benefits were keeping people from seeking work. Instead, April’s disappointing overall jobs numbers were driven by workers who went from employed to not in labor force. And since workers who leave the labor force are not eligible for unemployment benefits, enhanced benefits cannot be the reason for this trend.

Women accounted for nearly all of the increase in workers moving out of the labor force in April. Typically, women leave the labor force because of caregiving responsibilities. With more than a quarter of school districts nationwide still not fully open, there is still a large barrier for parents to return to a full-time, traditional work schedule. Lack of access to child care — not unemployment benefits — appears to be contributing to April’s disappointing jobs numbers, and could potentially remain a factor until schools fully reopen in the fall or access to child care is increased.

Other economic indicators suggest that the economy is simply adjusting from the pandemic and will need more time before things begin to look normal. For instance, job openings have spiked in the past few months as vaccinations increase and warm weather approaches. In particular, job openings in the food service and accommodation industry are up sharply, from 657,000 in January to 993,000 in March. But while that is a rapid increase, the overall level of job openings is pretty typical relative to pre-pandemic levels. The number of food service and accommodation job openings in March of 2019 was 918,000, with a peak of 1,024,000 in January of 2019. So while the labor market will likely need time to adjust to the rapid increase in the number of job openings as the economy recovers from the pandemic, the overall level of openings is not out of the ordinary.

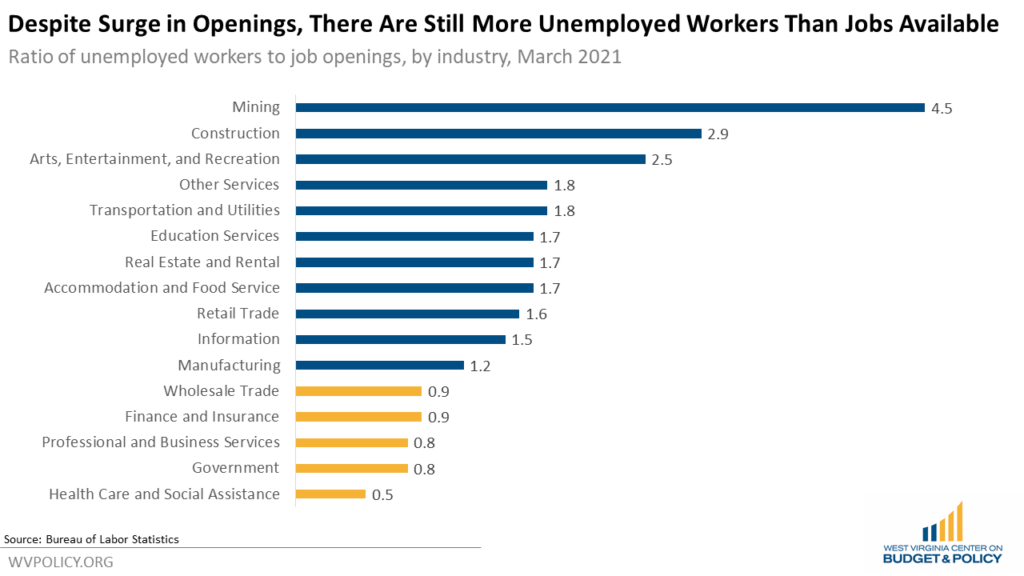

But despite the increase in job openings, there are still more unemployed workers than job openings. In March there were 9.8 million unemployed workers compared to 8.1 million job openings, or a ratio of 1.2 unemployed workers to every job opening.

The ratio is even higher in low-wage industries like food service and retail. In fact, only in the finance, professional and business services, wholesale trade, health care, and government sectors are there more job openings than unemployed workers. Once again, this is the opposite of what you would see if unemployment benefits were keeping people from working.

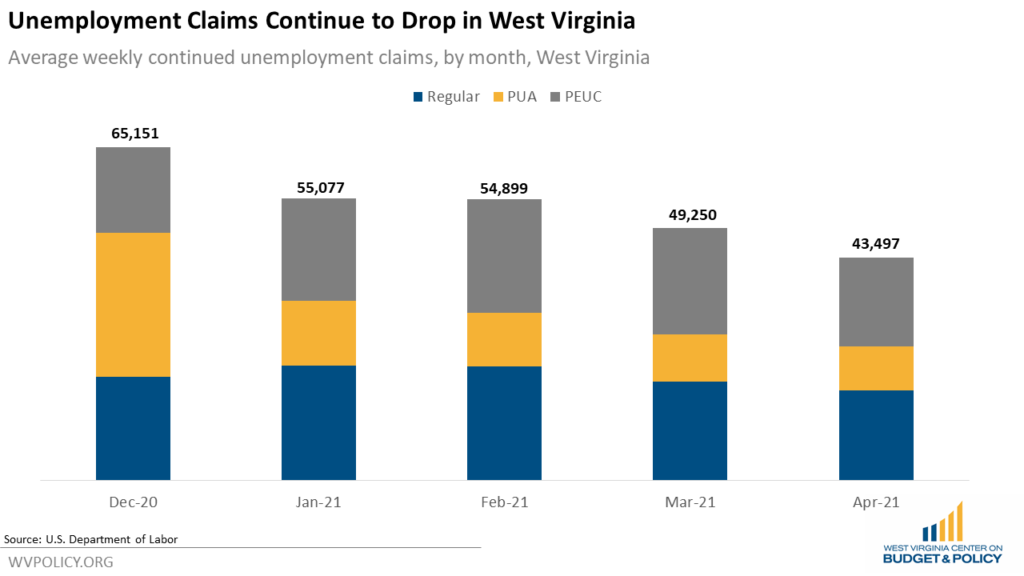

While there are still more job openings than unemployed workers, more workers are joining the labor force and the number of workers claiming unemployment benefits is dropping sharply. 827,000 workers have joined the labor force since January, while there were 2.6 million fewer workers claiming unemployment benefits in April than there were in December, a decline of 13.6 percent. The decline in unemployment claims in West Virginia is even sharper, with 21,000 fewer claims in April than in December, a decline of 33.2 percent.

All of this data suggests that rather than a fictitious scenario of lazy workers abusing pandemic unemployment benefits to avoid going back to work, we are instead experiencing an economy undergoing a major adjustment as it emerges from a global pandemic. Job openings are increasing rapidly, but the sectors that would be most likely to be affected by extra unemployment benefits are the ones adding the most jobs. The labor force is growing, and more and more people are leaving the unemployment insurance system and gaining employment, but there are still more job seekers than available jobs. Things are moving rapidly as the economy opens up, and it will take time for the labor market to adjust. All the while, significant barriers to employment still exist, from access to child care to legitimate health concerns about returning to work.

Meanwhile, the federal enhancements to the unemployment system are continuing to ease the transition, reduce hardship, boost spending, and contribute to the recovery, while also improving the labor market by encouraging higher wages for jobs that have been made harder and riskier because of the pandemic. Prematurely ending these benefits based on tired and discredited claims that people don’t want to work — as has already been suggested by Governor Justice — would do little to boost employment, and instead would needlessly hurt struggling workers and undermine the state’s economy and recovery.